2008: Conference at Moscow, Russia.

Report on the 8th SICAMM and 1st Russian International Conference, 'Apiculture in the XXIst Century; The Dark Bee In Russia',

Moscow, 2008

Russia is vast, over 4000 miles across and most of it unknown to the west. Many of us have vivid memories of Eric Milner’s description of the post-Ice Age colonization of Europe by dark bees, of how they burst from their glacial refuge in Iberia to spread and settle from Cap St Vincent to the Ural Mountains. My first insight into what that vast country has to offer was a map by Professor Nikolay Krivtsov showing dark bees spreading through the freezing forests of Bashkiria, right across the Ural Mountains and way, way beyond.

Bashkiria is a place the Russians speak of with awe. There temperatures average -2ºC and in winter drop to -45! Traditional forest beekeeping is still practised in the Shulgan-Tash Forest Reserve, with upright log hives mounted on platforms lashed high in pine trees, above the reach of bears, and cavities are excavated within tree boles and baited with old comb to attract swarms. In bear country bees attack your nose and eyes, because those are all that’s exposed on a bear, explaining why they raid bees’ nests with one paw over their faces. Bears carry hives to water and dump them in, then take out the frames one by one and wash off the bees, before gobbling up the brood and stores. I was given a toy with a carved wooden bear operated by strings attached to a pendulum, swatting bees attacking him from a hive, the roof of which he has pushed off.

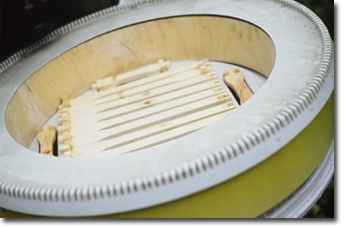

We were taken to a teaching apiary in the Ismailovskiy forest on the outskirts of Moscow established 300 years ago for the Tzar. It is also a centre for falconry and the falconer, stunningly attired in scarlet velvet and gold, flew a saker falcon around us, while a goshawk looked on. The apiary contained ornately decorated green and gold cylindrical log hives commemorating the Tzar and Tzarina. A modern version, designed by the present mayor of Moscow, is a 4ft yellow plastic cylinder with Styrofoam insulation and cartoon bees on the outside. It had a circular brood box and supers, each containing a nest of frames, ingeniously enmeshed in bold defiance of the Reverend Langstroth.

In more conventional box hives the bees are over-wintered by application of novel swivelling frame lugs that allow you to rotate the brood combs through 90º. In winter the cells are therefore orientated sideways, being returned to normal in spring. This, they claim, starts the bees off in excellent fettle. (All I can see it might do is allow the beekeeper to dictate when the queen will start laying.) They also had banks of mating nukes, each with a long brood comb folded in three, that when opened can be inserted into a standard broodbox.

The native bee of Russia is the Central Russian Forest Bee, which includes 22 or more distinct populations of A.m.mellifera in some 3.5 million colonies. These bring in 50,000 tons of honey out of a total 2 million tons per annum from all honeybee subspecies. In some areas genetic contamination of the native bee is a problem, but they claim great success with a native, but artificial strain, the Orlovsky Bee. This is resistant to Nosema and one colony can garner an incredible 400kg of honey from the taiga Willowherb they call Kipri, bringing in up to 24kg of honey per day!

The conference attracted 151 attendees, including 134 representatives of 190 regions of Russia, and a dozen or so other countries. BIBBA was represented by 2 members (Jo Widdicombe and myself) and SICAMM by 7, but despite our low numbers we gave a good account of ourselves, delivering some of the most interesting and well presented talks and planning future collaborations between “East” and “West” with the Director of the Bee Research Institute for the whole of Russia. Ole Hertz amazed us again with his pioneering introduction of the seriously threatened Laesø bee to alternative sites. These include several other Danish islands, on one of which he can sell “native bee honey” for £100 a kg. In Southern Greenland his Læsø Bee colonies bring in 80kg per season, but sometimes have to be excavated from snowdrifts in spring, so he marks them with masts. The Danish government funds promotion of native breeds and despite the social problems on Læsø, they are making money available to protect the Laesø bee.

Per Thunman told us of several new mating apiaries in Sweden. A.m.mellifera does especially well in the far north, even beyond the Arctic Circle, bringing in up to 70 kg of honey. Their problems include bears and shortage of drones, but average an 85% mating success. For the first time in recent years bears have become a factor in Switzerland, but Balser Fried concentrated on his problems and some success in correlating morphometry with microsatellite DNA variants in Swiss bees. He reported that when raised on worker foundation 4.9 instead of 5.1 mms between cell centres, A.m.m. (but not the other races) showed greatly reduced susceptibility to varroa, without reduction in honey yield. The concept behind this experiment seemed unknown to the Russians who favour large brood cell size. I presented an overview of DNA research on honeybees and the inferences we can draw from it, which immediately stimulated plans for a new research project.

My knowledge of Russian is limited to about 8 words and those didn’t come up all that often, so much of the programme remained a mystery, though we were given an English version of the lecture titles and someone translated interesting snippets. These included presentation of a comb-like temperature multiprobe that was used for plotting temperature profiles throughout the brood nest. Another described and compared entrained broodnest development programmes for bees collected in northern, central and southern regions. One I almost understood involved an apitherapist pretending to sting a “patient” on the thigh, calf and foot at positions I recognised as acupressure points for sciatica. The therapist then inserted his arm between the “patient’s” legs, grasped his hip from behind and made some violent jerking movements, which I deduced were aimed at freeing a trapped sciatic nerve. He then stripped off his (own) shirt, rolled down his trouser top and demonstrated stinging his naked abdomen to improve the functioning of the genitalia. It caused considerable mirth, but would have been even more entertaining if he had succeeded in persuading the cute little blonde in the short skirt to be his “patient”.

The Russians consider spontaneous amiability to be the mark of a simple mind, so their body language tends to create a negative impression in us - until they speak in English, when everything changes and their warmth and generosity shine through. As President of SICAMM I was treated like a visiting dignitary and indeed we were the first westerners to visit that academy. It was I believe, a ground-breaking conference, opening up new worlds both for us western honeybee conservationists and for like-minded people in the former Soviet Union. Major outcomes were the enthusiasm of the Russians to exchange scientists with universities in the west and our negotiation of a collaborative genetic research programme between them and the French DNA analysts with whom we became acquainted at Versailles.

A cultural evening of Georgian singing and dancing before a vast audience at the Kremlin was remarkable for its energy, sustained “points work”, the deep growling songs of the men and the line of guards separating us from the performers. Despite their usual seriousness, the Russians certainly know how to party. Lunch at the apiary was a table-creaking affair with many rousing toasts in vodka and great chunks of wild honeycomb we spread on rough bread and ate with slices of lemon. The conference was, rounded off with a lively session of live music and caviar and other delicacies washed down with vodka and wine.

The second International Russian Dark Bee Conference will be in Bashkiria, in 2010, where we should see traditional beekeeping amid the pine forests and perhaps bears! Meanwhile we look forward to September 2009, when SICAMM will hold its ninth conference at Aviemore in the Highlands of Scotland, surely the most exciting (and accessible) conference location in Britain. Put it in your diary now!

Dorian Pritchard

A scene in the Ismailovskiy teaching apiary showing reproductions of the original vertical log hives of 300 years ago. The nearest green and gold hives are named in honour of the Tzar and Tzarina.

A modern vertical cylinder hive designed by the current mayor of Moscow.

The interior of the mayor’s hive.